Across the Western world, the age at which women become mothers has steadily increased over the past several decades, reflecting profound social, economic, and cultural shifts. In the mid-20th century, first births commonly occurred in a woman’s early to mid-20s, closely tied to earlier marriage and more traditional life trajectories. Today, however, the average age at first birth in most Western countries has moved into the late 20s or early 30s, with a growing proportion of women having their first child at 35 years or older. This trend is observed across North America, Western Europe, Australia, and parts of East Asia with similar socioeconomic structures, making delayed motherhood a defining demographic feature of high-income societies.

Several interconnected factors drive this shift toward older maternal age. Expanded access to higher education and professional opportunities has led many women to prioritize academic and career development during their 20s, often postponing family formation until greater financial stability is achieved. Economic pressures, including housing costs, student debt, and job market insecurity, further incentivize delay. At the same time, reliable contraception and broader reproductive autonomy have given women more control over the timing of pregnancy, while changing social norms have reduced stigma around later marriage, non-marital childbearing, and delayed parenthood.

The aging of mothers at birth has important biological, medical, and societal implications. From a health perspective, advancing maternal age is associated with declining natural fertility, higher rates of infertility and pregnancy loss, and increased risks of complications such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, placental abnormalities, and cesarean delivery. There is also a gradual rise in chromosomal abnormalities with age. However, these risks exist alongside notable benefits: older mothers are, on average, more educated, financially secure, and emotionally prepared, factors that are strongly associated with positive child developmental outcomes. Advances in obstetric care, prenatal screening, and assisted reproductive technologies have also mitigated many age-related risks, making later motherhood increasingly feasible.

At a population level, delayed childbearing contributes to broader demographic changes in the Western world, including lower total fertility rates and population aging. As women have children later and often have fewer children overall, societies face challenges related to workforce replacement, healthcare demand, and social support systems. In response, many countries have expanded access to fertility treatments, parental leave, and childcare support, while public health discussions increasingly emphasize realistic education about reproductive aging. Together, these trends illustrate how the rising age of mothers at birth is both a reflection of modern women’s expanded life choices and a central issue shaping the future demographic and health landscape of Western societies.

The ovary follows a predictable but steep aging trajectory, with both egg quantity and egg quality declining long before menopause becomes apparent. Females are born with roughly one to two million oocytes, but only about 300,000 to 500,000 remain by puberty. From the mid-20s onward, the number of available eggs (ovarian reserve) begins to fall steadily, but the most clinically significant drop occurs around age 32, followed by an even sharper decline after age 37. Alongside this quantitative loss, egg quality deteriorates due to accumulating chromosomal errors, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and impaired spindle formation within the oocyte. This decline in quality, not just quantity, reduces the likelihood that an egg will fertilize normally and develop into a healthy embryo. By the late 30s and early 40s, the proportion of eggs with chromosomal abnormalities rises rapidly, driving lower natural conception rates, higher miscarriage risk, and reduced success even with advanced fertility treatments such as IVF. Ultimately, ovarian aging reflects a dual process of diminishing egg supply and escalating genetic instability within remaining oocytes, both of which progressively limit fertility well before menopause occurs.

For fifty years, something fascinating has been happening to human intelligence. And the story is not what most people expect. From the 1950s through the 1990s, IQ scores were rising across the world. This surge was so consistent that scientists named it the Flynn Effect. People weren’t genetically smarter. Our environments were. Better nutrition. More education. Fewer toxins like lead. And a world that pushed kids to think abstractly. All of it boosted problem-solving skills by about two to three points every decade. But around the late 1990s, something changed. In many developed countries, IQ scores stopped rising. In some places, they’ve even begun to fall. This decline is small, about one to three points per decade, but researchers are paying attention. Why is it happening?

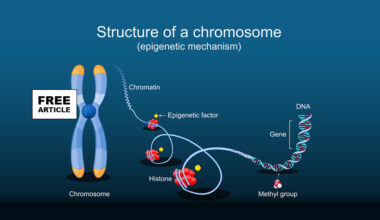

Epigenetic changes have been proposed as one potential contributor to the subtle declines in population-level IQ scores observed in several countries over recent decades, though the evidence is still developing. The central idea is that modern environmental pressures, such as increased exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (like BPA, phthalates, PFAS), chronic low-grade inflammation, poor diet quality, sedentary lifestyles, and even rising parental stress may influence the way genes involved in neurodevelopment are expressed without altering the DNA sequence itself. These influences often act through DNA methylation, histone modification, and changes in non-coding RNA activity, which can alter neuronal growth, synaptic pruning, and cortical maturation during fetal development and early childhood. Some studies have identified associations between environmental toxicants and altered methylation of genes critical for brain development, with corresponding reductions in working memory, processing speed, or executive function in children. Additional research suggests that epigenetic effects may accumulate across generations: for example, maternal stress or nutritional deficiencies can produce methylation patterns that affect offspring cognitive outcomes, and some of these marks may persist into subsequent generations. While epigenetics may not be the sole driver of IQ trends, education systems, technology use, and social factors also shape cognitive performance, it is increasingly recognized as an important biological pathway that links modern environments to subtle shifts in population-level cognitive measures.

In the 1940s and 1950s, autism was barely recognized as a diagnostic category. The condition first gained clinical recognition in 1943, but for years afterward autism was considered extremely rare and often only identified in the most severe cases. In the 1960s and 1970s, early prevalence studies estimated roughly 2 to 4 cases per 10,000 children (i.e. ~0.02%–0.04%), a reflection likely of narrow diagnostic definitions, a focus on severe “classic autism,” and limited awareness. Starting in the late 1970s and especially into the 1980s and 1990s, the concept of autism broadened, clinicians and researchers began recognizing milder and more diverse presentations, and the idea of an “autism spectrum” gained traction. As diagnostic criteria expanded (for example through successive revisions of the diagnostic manual), reported prevalence increased.

By around the year 2000, in the United States the reported prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder ASD as measured through regular national surveillance efforts by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had reached about 6.7 cases per 1,000 children (≈ 1 in 150). Over the next two decades the numbers rose steeply: by 2010, prevalence among 8-year-olds had more than doubled. In the most recent data from the CDC’s ongoing surveillance, as of 2022 (birth year 2014 cohort) about 1 in 31children (≈ 3.2%) were identified with ASD.

Overall, what this history shows is a dramatic rise from a condition once considered very rare to one recognized in a few percent of children today. However, most experts caution that much of that rise reflects expanding definitions of autism, increased awareness, better screening.

Epigenetics plays a significant role in the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by influencing gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. These heritable modifications include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and regulation by non-coding RNAs, all of which can alter the activity of genes involved in neurodevelopment, synaptic function, and neural circuitry. Abnormal DNA methylation patterns have been observed in genes critical for brain development, leading to either overexpression or silencing of key genes that regulate neuronal growth, connectivity, and communication. For instance, hypermethylation of genes involved in synaptic plasticity can impair neural signaling, while hypomethylation of genes linked to immune responses may contribute to neuroinflammation, both of which have been associated with ASD. Histone modifications alter chromatin structure and gene accessibility, influencing expression levels of neurodevelopmental genes. Additionally, dysregulation of microRNAs can disrupt the balance of gene networks essential for proper brain maturation. These epigenetic changes are often influenced by environmental factors such as prenatal stress, toxins, and maternal nutrition, which can trigger or exacerbate neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Epigenetic changes are also linked to anxiety and depression in children and center on how early-life environments, especially stress, trauma, nutrition, and inflammation modify gene expression in brain circuits that regulate mood and stress responses. One of the most studied pathways involves the Hypothalamus Pituitary Adrenal axis HPA axis, the body’s central stress-regulation system. Chronic prenatal or early-childhood stress can increase DNA methylation of the NR3C1 gene, which encodes the glucocorticoid receptor responsible for shutting down the stress response after a threat has passed. When this receptor is epigenetically “silenced,” cortisol remains elevated for longer periods, leaving children biologically predisposed to anxiety, emotional reactivity, and difficulty regulating fear. Similarly, methylation changes have been observed in the FKBP5 gene, which modulates cortisol signaling; reduced methylation here can lead to overactive stress circuits and heightened vulnerability to both anxiety and later-life depression.

Epigenetic changes also affect the brain networks responsible for mood regulation, particularly the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. Early adversity, neglect, conflict, or inconsistent caregiving can alter histone modification and microRNA activity in these regions, impairing synaptic plasticity and altering the balance of excitatory and inhibitory signaling. These changes may make the amygdala more reactive to emotional stimuli and weaken prefrontal circuits responsible for calming the fear response, increasing the likelihood of anxiety disorders. In depression, key genes involved in neuroplasticity especially BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) often show increased methylation, reducing the brain’s ability to form healthy neural connections, particularly in the hippocampus. Reduced BDNF expression has been linked to lower resilience, impaired emotional learning, and a greater risk of depressive symptoms emerging during childhood and adolescence.

Inflammation-related epigenetic changes also play a significant role. Maternal infections, poor prenatal nutrition, or chronic stress can alter methylation in immune-regulating genes, creating a pro-inflammatory biological state that affects developing neural circuits involved in mood and cognition. Children with these patterns are more likely to show irritability, low mood, and reduced stress tolerance. Importantly, many of these epigenetic changes are plastic and potentially reversible. Warm, predictable caregiving, enriched environments, social support, adequate nutrition, physical activity, and stress-reduction programs have all been shown to modify epigenetic marks and improve emotional outcomes, highlighting the central role of environment in shaping long-term mental health.

Egg Freezing has emerged as a viable strategy to overcome the natural decline in egg quality. Egg freezing is most effective when done before age-related declines in egg quality and quantity accelerate, which is why specialists generally recommend freezing eggs between ages 30 and 35, with the early 30s considered ideal. At this stage, ovarian reserve is still relatively strong, and the proportion of genetically healthy (euploid) eggs is significantly higher, translating to better future pregnancy outcomes. Freezing eggs before age 30 offers even higher egg quality, but many women have not yet made long-term reproductive decisions at that point.

Male aging is also a factor; men tend to have children at a much later age then their parents. Sperm freezing, or cryopreservation, is increasingly discussed as a strategy to preserve male reproductive potential in the context of aging because male germ cells, unlike female oocytes, are produced continuously throughout life and are therefore repeatedly exposed to cumulative biological stress. As men age, the spermatogonial stem cells that give rise to sperm undergo thousands of rounds of DNA replication. Each replication cycle introduces opportunities for copying errors, and over time this leads to a gradual accumulation of de novo point mutations, small insertions and deletions, and structural DNA changes in sperm. Freezing sperm at a younger age effectively “locks in” a genomic snapshot from a period when mutation burden is lower, reducing the likelihood that age-related genetic alterations will be transmitted to future offspring.

In addition to replication errors, aging is associated with increased oxidative stress within the testes and epididymis. Reactive oxygen species can induce DNA strand breaks, base modifications, and chromatin cross-linking in sperm, which are particularly vulnerable because mature sperm have limited DNA repair capacity. Although some DNA damage can be repaired after fertilization by the oocyte, this repair is incomplete and less efficient as maternal age increases. Cryopreservation halts metabolic activity and oxidative processes, thereby preserving sperm DNA integrity at the time of freezing and preventing the progressive accumulation of oxidative lesions that occurs with advancing paternal age.

Epigenetic integrity is another important component of the rationale for sperm freezing. Aging has been linked to alterations in sperm DNA methylation patterns, histone retention, and small non-coding RNAs, all of which play critical roles in early embryonic development and long-term offspring health. Age-related epigenetic drift in sperm has been associated in epidemiologic studies with higher risks of neurodevelopmental disorders, certain congenital anomalies, and complex diseases in offspring. By freezing sperm earlier in life, before substantial epigenetic remodeling or dysregulation occurs, it may be possible to reduce the transmission of age-associated epigenetic changes that could influence gene expression in the next generation.

Finally, the clinical and societal rationale for sperm freezing reflects shifting reproductive timelines. Many men delay fatherhood for educational, professional, or personal reasons, often well into their late thirties, forties, or beyond, when measurable increases in sperm DNA fragmentation and mutation rates are observed. Cryopreservation offers a proactive option to preserve higher-quality sperm from a younger biological age, potentially lowering risks linked to advanced paternal age while maintaining reproductive autonomy. In this context, sperm freezing is not about guaranteeing outcomes, but about reducing one modifiable biological risk factor age-related DNA and epigenetic modification at a time when male reproductive aging has historically been underappreciated.