Advances in reproductive medicine are opening doors that were unimaginable just a generation ago, particularly for women concerned about inherited disease and fertility loss. Emerging technologies such as mitochondrial replacement therapy, gene editing, and the development of artificial gametes promise new ways to prevent severe genetic disorders and expand reproductive options. For women who carry known genetic mutations or who have lost fertility due to age, cancer treatment, or medical conditions, these innovations offer the possibility of having healthy, genetically related children; an outcome that until recently was often out of reach.

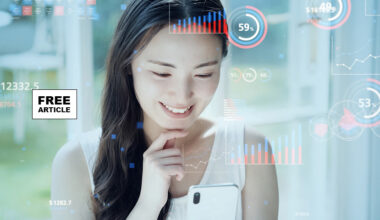

Mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT) is an assisted reproductive technology designed to prevent the transmission of inherited mitochondrial diseases from mother to child. Mitochondria are the energy-producing structures within cells, and unlike most DNA, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is inherited exclusively from the mother. In women who carry pathogenic mutations in their mtDNA, these defects can lead to severe, often life-threatening disorders affecting high-energy organs such as the brain, heart, muscles, and liver. Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy (MRT) works by separating the nuclear genetic material, which contains nearly all of a person’s genes from the mother’s defective mitochondria and transferring it into a donor egg or embryo that contains healthy mitochondria but has had its own nuclear DNA removed. The reconstructed egg or embryo is then fertilized or implanted, resulting in a child who inherits nuclear DNA from the intended parents and healthy mitochondrial DNA from the donor.

There are two main MRT techniques: maternal spindle transfer, performed before fertilization, and pronuclear transfer, performed shortly after fertilization. In maternal spindle transfer, the mother’s nuclear DNA is removed from her unfertilized egg and inserted into a donor egg with healthy mitochondria that has been enucleated, after which the egg is fertilized. In pronuclear transfer, both the mother’s egg and a donor egg are fertilized first; the pronuclei containing the parents’ nuclear DNA are then transferred into the donor embryo after its pronuclei have been removed. Both methods aim to minimize the carryover of defective mitochondria. Clinically, MRT is viewed as a targeted, preventative strategy for families at high risk of mitochondrial disease, rather than a form of genetic enhancement.

Gene editing of embryos refers to the deliberate alteration of DNA in a human embryo at the earliest stages of development, typically using molecular tools designed to precisely modify specific genes. The most widely discussed technology is CRISPR-Cas9, which acts like a programmable pair of molecular scissors: it is guided to a targeted DNA sequence, cuts the DNA, and then relies on the cell’s natural repair mechanisms to disable a gene, correct a mutation, or insert new genetic material. Gene Editing could prevent severe inherited disorders such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, or certain forms of muscular dystrophy by correcting disease-causing mutations before birth. When applied to embryos, these edits occur at the single-cell or early multicellular stage, meaning that any genetic change can be propagated to all cells of the developing individual, including germ cells. This makes embryonic gene editing fundamentally different from gene editing in children or adults, where changes affect only the treated tissues and are not inherited by future generations.

Artificial gametes are laboratory-derived reproductive cells, sperm or eggs, created from non-reproductive cells using advanced stem-cell and developmental biology techniques. The process typically begins with somatic cells, such as skin or blood cells, which are reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells capable of giving rise to many different cell types. These stem cells are then guided, through carefully controlled chemical signals and growth environments, to follow the same developmental pathways that naturally produce primordial germ cells and eventually mature into sperm or oocytes. In animal models, particularly mice, researchers have successfully generated functional artificial gametes that can produce healthy offspring, demonstrating the biological feasibility of this approach, although the process in humans remains experimental and incomplete. The potential implications of artificial gametes are far-reaching for reproductive medicine and society. Clinically, they could offer new fertility options for individuals who cannot produce viable gametes, including cancer survivors, people with certain genetic or developmental conditions, same-sex couples, or individuals beyond typical reproductive age.

These developments raise profound ethical concerns, particularly around germline modification; genetic changes that are passed from one generation to the next. Unlike most medical interventions, these technologies do not affect only one patient or one child; they may permanently alter a family’s genetic legacy. This raises difficult questions about consent, responsibility, and the moral weight of making decisions that will shape future generations who have no voice in the process.

Another major concern is uncertainty about long-term safety. Because these technologies are new, scientists do not yet know how genetic changes might interact with biology, environment, or aging over decades. Small alterations made with good intentions could potentially have unforeseen consequences years later. For women, who often carry both the physical risks of reproduction and the emotional responsibility for reproductive decisions, this uncertainty can be especially challenging.

There are also broader social implications to consider. As genetic technologies become more advanced, fears have emerged about a slippery slope from disease prevention to genetic enhancement. The possibility of selecting traits beyond health raises concerns about inequality, social pressure, and the definition of what is considered “normal” or “acceptable.” Women already face intense scrutiny around pregnancy and parenting choices, and these technologies may add new layers of expectation and judgment.

Access and equity further complicate the picture. Advanced reproductive technologies are costly and unevenly regulated, meaning they may be available only to a small, privileged segment of the population. This raises concerns about widening health disparities and the potential exploitation of women as egg donors or surrogates, particularly in settings where oversight is limited.

For women engaging with these issues, whether as patients, professionals, or informed citizens, the challenge lies in balancing hope with caution. Emerging reproductive technologies have the potential to reduce suffering and expand reproductive autonomy, but they demand careful ethical oversight, transparent research, and inclusive public dialogue. As science moves forward, women’s voices will be essential in shaping how these powerful tools are used, ensuring that progress serves not only medical possibility but also long-term human well-being.