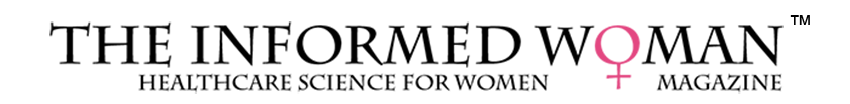

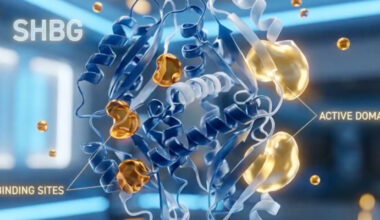

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a complex endocrine disorder characterized by an interplay between genetic, metabolic, and hormonal abnormalities that lead to ovarian dysfunction, hyperandrogenism, and metabolic disturbances. The pathophysiology begins with insulin resistance, which occurs in many but not all women with PCOS and contributes significantly to its endocrine and metabolic features. Insulin resistance leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which enhances ovarian theca cell production of androgens and simultaneously reduces hepatic synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), increasing the levels of free circulating androgens. Elevated androgens disrupt the normal follicular development process in the ovaries by impairing follicle maturation, leading to an accumulation of small antral follicles and the characteristic appearance of “polycystic” ovaries on ultrasound. Additionally, hyperandrogenemia interferes with hypothalamic-pituitary regulation, causing an increased frequency and amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses. This favors, luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion over follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), further driving theca cell androgen production while depriving developing follicles of adequate FSH stimulation needed for maturation and ovulation. The resulting chronic anovulation manifests clinically as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea. In addition, low-grade inflammation and adipose tissue dysfunction contribute to the hormonal imbalance and insulin resistance, perpetuating the cycle of metabolic and reproductive disturbances. Thus, PCOS represents a multifaceted disorder involving disrupted communication between the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, altered insulin signaling, and metabolic dysregulation.

In polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis becomes dysregulated in a way that reinforces chronic anovulation and androgen excess. At the hypothalamic level, women with PCOS often exhibit an abnormally rapid gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulse frequency. Faster GnRH pulses favor the synthesis and secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) over follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), producing the characteristic elevation in the LH-to-FSH ratio. This elevation drives the ovarian theca cells to produce excess androgens, particularly testosterone and androstenedione. Meanwhile, relatively low or inappropriately normal FSH levels impair granulosa cell function and compromise follicular maturation, leading to the arrest of multiple small antral follicles rather than the selection of a dominant follicle for ovulation. The resulting anovulation perpetuates low progesterone levels, which removes the normal luteal-phase slowing of GnRH pulsatility, allowing high-frequency GnRH pulses to continue unchecked. Insulin resistance—common in PCOS—further amplifies the dysfunction by enhancing theca-cell androgen production and lowering sex hormone–binding globulin, increasing free androgens. Together, these alterations create a self-reinforcing loop within the HPO axis: disturbed GnRH pulsatility elevates LH, excess LH drives androgen excess, low FSH prevents normal follicle development, and absent ovulation prevents the hormonal feedback needed to restore normal neuroendocrine rhythm.

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) plays a significant and multifaceted role in the pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), reflecting and contributing to the characteristic ovarian dysfunction. In PCOS, AMH levels are often two- to four-fold higher than in women without the condition because the ovaries contain an increased number of small antral follicles—the very structures that produce AMH. Beyond being a marker of follicle number, AMH directly alters the physiology of the ovary and the broader reproductive axis. At the ovarian level, AMH inhibits the initial recruitment of primordial follicles and reduces the sensitivity of growing follicles to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), making it more difficult for any single follicle to become dominant and proceed to ovulation. This amplifies the chronic follicular arrest seen in PCOS. AMH also appears to enhance androgen production by increasing the responsiveness of theca cells to LH, thereby reinforcing the hyperandrogenic environment. At the hypothalamic–pituitary level, emerging evidence suggests that AMH may increase GnRH neuron activity and raise LH pulse frequency, linking elevated AMH to the abnormal neuroendocrine signaling characteristic of PCOS. Thus, elevated AMH is not merely a biomarker but an active participant in the disrupted feedback loops of PCOS, contributing to anovulation, androgen excess, and the persistence of the syndrome’s reproductive and hormonal abnormalities.